TRANSLATION OF THE MALAY BIBLE - Terminologies | GOH LAY HUA

The development of religious terminology in the translation of the Malay Bible: A case study of the cross-cultural communication in the Malaysia context | Goh Lay Hua

Paper was published as a proceeding in the International Conference of Translation ICT-16, 2017

Abstract

The development of religious vocabulary used in the translation of the Malay Bible in addressing the cross-cultural communication peculiar to the Malaysian context spans over a history of over 400 years of bible translation in Malay. Numerous translations were printed and circulated. However, the character of these various translations varied considerably. As most of the early translations were undertaken by foreign agencies from different colonial nations, one could expect to witness the vast variants in the use of lexicons and the different translation philosophies. One of the most crucial factors that resulted in the ongoing translation effort of Bible translation in Malay since the early 17th century up to recent times is the profound impact of the rapid changes in the Malay language itself. Evidently, even up to the present time, Bible translators whose focus are not just religious but literary have made deliberate lexical choices that further defined a distinct set of Christian religious terminology which are not just new coined vocabulary but also largely unused or unknown outside the Christian community.

This article will focus on three major factors that contributed to the development of religious terminology in the Malay Bible in a pluralistic society like Malaysia with different religious and political ideologies, languages and culture. These three factors namely situational linguistics, non-lexical equivalence in Malay and socio-cultural factors that distinctively shaped the development of biblical vocabulary over the decades.

1. Historical overview of Bible translation in the Malay-speaking world

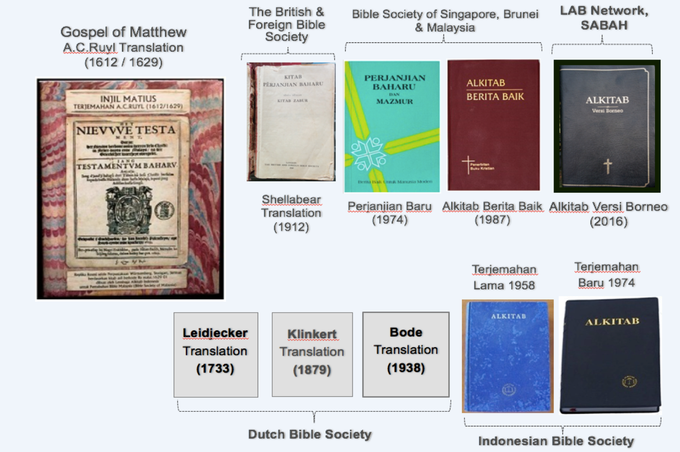

The development of religious vocabulary in the translation of the Bible stretches as far back as 17 century when the first translated Gospel of Matthew was published in 1629. Translated by Albert C. Ruyl, Jan Van Hasel and Justus Heurnius and published under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company, the translation of this gospel of Matthew could be said to have ignited the interest in Bible translation in Malay. It essentially paved the way for subsequent translations of more portions of the Bible in Malay. In 1733, the first complete version of the whole Malay Bible known as the Leydekker’s translation was printed. This Bible version became the standard translation until mid 19th century. The translation took place in the era when the European colonialism was rapidly developing in South East Asia, a region known for its ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity. All the earliest translations were undertaken by the Dutch and were done in Jawi script. Only towards the later part of the 19th century and early 20th century, Bible translations were done by the British and the Americans.

Most of these early translations chose High Malay as the translators and officials in the Dutch Colonial government were not in favor of using Low Malay or what is commonly known as Bazaar Malay. Low Malay had long been a lingua franca, or trade language used in ports and markets. It assumed many forms, depending upon varying regional influences on grammar and vocabulary of the local tongues, Chinese and European languages. This Low Malay later developed into Ambonese Malay of the Ambon Islands of Indonesia and the Baba Malay of Malacca.

There were also translations of the Bible into Baba Malay of Malacca, a southern state in Malaya. Baba Malay is a distinctive Malay which incorporated many words from Hokkien, English, Portuguese and Dutch into its vocabulary. One such significant translation was the translation of the New Testament undertaken by W.G. Shellabear and which was first printed in 1912. Since its publication, it had been in continuing use by the Peranakan Christians up to the present day. The term Peranakan literally means descendants or locally born in Malay. It refers to the descendants of the Chinese immigrants to the Straits Settlements which comprised the states of Penang, Malacca and Singapore.

As for the more recent works, a translation using modern Malay with the new spelling system is the Malay Bible known as Berita Baik Untuk Manusia Moden (Good News for Modern Man) published in 1987 by the Bible Society of Malaysia.

The latest and most up to date translation of the Malay Bible is Alkitab Versi Borneo (AVB), also known as Borneo Bible Version, was published by LAB Network and first released in January 2016. AVB which took over 15 years to complete was undertaken by a nucleus team of key translators, eminently qualified linguists and educationists with fluency in classical and modern Malay. Greek and Hebrew scholars and reviewers also played a major part in the biblical accuracy and theological meaning of this translation. Modern translation software and tools were utilized to the fullest to achieve significant progress on consistency of words, rendering of biblical terms, harmonization of parallel Bible passages, and ensuring fidelity to the original languages.

For Christians who use the Malay language (Bahasa Malaysia), the majority of whom are indigenous Christians (sons of the soil), an accurate and scholarly translation of the Bible, based on the original languages, is a high priority for them. AVB is credited as a good translation and reviewers attested that AVB has the hallmarks of a good translation - accuracy, clarity, naturalness and acceptability.

Table 1 - A summary of Malay translations of Various Portions of the Bible

|

Year |

Segment |

Notes |

|

1638 |

Matthew, Mark |

Translated by the Albert C. Ruyl, Jan van Hasel, and Justus Heurnius, and published under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company. |

|

1646 |

Luke, John |

|

|

1651 |

Gospels, Acts |

|

|

1652 |

Psalms |

|

|

1662 |

Genesis |

Translated by Daneil Brouweius, a Dutch minister. |

|

1668 |

New Testament (The first New Testament to be translated) |

|

|

1733 |

Bible (Arabic script) |

Translated by Melchior Leydekker, a Dutch minister in Batavia, who completed the Old Testament and the most of the New Testament before his death. The New Testament was completed by Pieter van der Vorm, and then the whole Bible was revised by C . H. Werndly, A. Brants and E. C. Ninaber. |

|

1817 |

New Testament (Arabic script) |

- |

|

1821 |

Bible (Arabic script) |

A revision of the 1733 Bible, prepared by J. MacInnes, an army major, and R. S. Hutchings, and Anglican chaplain. |

|

1820-1824 |

Bible (Arabic script) |

A revision of the 1733 Bible, prepared for the NBS by J. Willmet |

|

1828 |

Matthew (Arabic script) |

- |

|

1831 |

New Testament (Arabic script) |

A revision of the 1817 N. T., prepared by Claudius H. Thomsen, London MS, and Robert Burn, an Anglian chaplain. |

|

1850 |

Matthew |

Translated by K. T. Hermann, Netherlands MS. |

|

1853 |

New Testament |

A revision of the 1831 N. T., prepared by S. Dyer, J. Evans, and B. P Keasberry, LMS. |

|

1856 |

New Testament (Arabic script) |

|

|

1866 |

New Testament |

A further revision by B. P. Keasberry, LMS, who published portions, e. g. Psalms, etc., in his own translation as early as 1847. |

|

1868 |

Matthew |

Translated by H. C. Klinkert, a Dutch Missionary. In 1887-1889, this Bible appeared transliterated into Arabic script. |

|

1870 |

New Testament |

|

|

1871 |

Genesis |

|

|

1879 |

Old Testament |

|

|

1897 |

Matthew |

A revision prepared by a committee supervised by W. G. Shellabear. |

|

1901 |

Mark (Arabic script) |

|

|

1910 |

New Testament, Genesis, and Psalms (Arabic script) |

|

|

1912 |

Old Testament (Arabic Script) |

|

|

1932 |

Luke |

Translated by W. A. Bode and others. This revision, published with the Klinkert Old Testament, is also used by Indonesian Christians. |

|

1938 |

New Testament |

|

|

1974 |

New Testament |

First edition of the New Testament translation (Perjanjian Baru, Today’s Malay Version) |

|

1987 |

Bible |

Publication of the Old and New Testaments together in the Alkitab (Today’s Malay Version) by the Bible Society of Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei. |

|

2016 |

Bible |

Publication of the Alkitab Versi Borneo, a project undertaken by the indigenous Christians for their own Christian communities. |

While the long history of almost 400 years of Bible translation in Malay has significantly contributed in the development of religious vocabulary, with many specialized terms often understood only within the church circles and not found in any of the known Malay dictionaries, many of the Biblical Malay vocabulary are constantly changing, evolving, and developing mainly to address the problems and issues in the cross-cultural communication of Bible content. Besides, most of the translated versions were done by foreign agencies with limited knowledge of the local language and culture. Hence, many words used are unlikely to be marked by accuracy of the original meaning. Many words which do not represent the actual meaning in the source text have remained in use (eg. domba for sheep instead of kambing biri-biri) due to the cumulative effect of its regular use in their worship.

Conversely, many words have also become obsolete or are replaced with new words in the latest Malay Bible that is Alkitab Versi Borneo. Theological words that have been traditionally used for centuries such as, Juruselamat (Saviour) is now recently replaced with penyelamat, keselamatan (safety) with penyelamatan (salvation), semesta alam (all the world)with alam semesta (cosmos, universe).

2. Factors that contributed to the development of religious vocabulary

The development of the religious vocabulary in Malay from the earliest times during the colonial days up to the most recent times of the publications of the AVB translation could be broadly categorized under three groups: the situational linguistics, non-lexical equivalence in Malay and socio-cultural factors. These factors significantly propelled the Bible lexicographer and translators alike into the coining of terms and contributed to the frequent changes and modification of the core religious vocabulary.

a) Situational Linguistics

One of the most prevailing factors that boosted the early development of Bible language in Malay is what I call the situational linguistics exerted by the immigrants to South East Asia.

Situational linguistics is a phrase I use to define the linguistic elements that contributed to the emergence or formation of a new form of expression of a language with all its lexicological, phonological, morphological, syntactical features to meet the situational language needs of the community or society. In other words, in meeting the communicative demands arising from the expanding cognitive needs of a community, new lexicon is often created. Translators have to grapple with situational linguistics in order to make their translation relevant to the needs of receptor cultures and communities. They have to contend with all the complex problems arising out of the need to express the ancient message of the Bible in the vernacular language. In the process, they constantly face the challenge of how to translate Biblical concepts, fauna and flora, practices, festivals, rituals, spiritual beings, cultural artifacts, metaphors, beliefs in terms that make communication meaningful and understandable to the receptors.

As seen in Table 1, the Bible translators in Malay are pioneers who initiated the biblical discourse in the local Malay language and thereby established religious words.

Over the centuries, beginning with the arrival of the Dutch colonial power in 1641 right through the British colonization in late 19th century, successive waves from foreign languages along with the large number of related dialects of Malay had exerted a significant impact on the early development of the religious lexicons used in the Bible. While Malay was used then as a common trade language and as a means of communication over an extensive area in South East Asia, biblical vocabulary in Malay did not really exist until foreign missionaries working under the colonial rulers began the task of bible translation. Endowed with the ability to assess a situation with respect to a receptor’s or hearer’s social, cultural or linguistic needs, bible translators opted to borrow loan words from Sanskrit, Arabic, Portuguese, Dutch, Chinese and Tamil. Over time driven by the local language situation, numerous loan words began to creep in the Malay translation of the Bible.

Eventually many of these words were assimilated in the Bible and become the established words used for many decades and some even till these days (see Table 2). One of the earliest Bibles in Malay which reflects such phenomenon of the prevailing use of loan words was the translation undertaken by Dr Melchoir Leydekker, a Dutch clergyman, who was apparently a gifted linguist. His translation was largely checked against the Arabic Bible at that time resulting in the assimilation of many lexical items with Arabic roots. The assimilation of these Arabic words could be clearly seen in the adoption of the Arabic names of the same biblical and quranic characters such as Adam, Musa, Nuh, Daud and Yusuf, Yahya. Other items used by Leydekker have also become the standard terminology used in some of the translations of the Malay Bible. Among the religious words used which have remained till today are Isa Al Masih, Dajal, Injil, Zabur, Taurat, kitab, nabi, ilmu. Although these biblical terms may not be completely the same as the Christian understanding, translators felt these Arabic loan words were adequate in conveying the biblical meaning.

Apart from the numerous Arabic loan words which were widely used in the early Bible text in Malay, were also words borrowed from the Sanskrit, which mostly come from the domains of religion and kinship such as syurga (heaven), neraka (hell), dosa (sins), pahala (reward), and singgahsana (throne). The Sanskrit words which crept into the Malay language were mostly brought about by the Hindu traders. The Portuguese and the Chinese also contributed to the list of loan words used in the Bible translation. For instance, the word, gereja, an established regular word in our vocabulary, derives from the Portuguese word, Igreja, which means church.

Early Bible translators also commenced a Bible translation in the Baba Malay Bible using mostly what we called the Bazaar Malay. The Baba Malay New Testament was first published in 1913 and incorporated many words and expression from Hokkien, English, Portuguese and Dutch into its vocabulary. Examples of such Chinese based words and expression which were literally transliterated into Baba Malay were used in the early Bible were cawan (cup), tuala (towel). The word, cawan, has become a symbolic object used in the Lord Supper described in the New Testament.

In so far, the earliest Bible translators in Malay felt warranted to experiment with the acquisition of existing words used either in written or oral transition from the various communities or from loan words. There were obvious limits of Malay used or spoken at the trade centers as many of the Biblical terms were not generally used or known. The limits of the Malay language at the time were also compounded by the many related Malay dialects.

However, as the Bible in Malay began to be used in the various regions in South East Asia including Indonesia, Brunei and Singapore, religious words gradually became entrenched. But as society changes, the use of language changes too. Some of the Arabic based words used as shown in the Table 2 were dropped from the Bible vocabulary as more recent Bible translators move away from what they perceived as disputed terminology.

b) Non-lexical equivalence in Malay

No aspect of translation is more complex, confusing and time-consuming than the problems of translating non-lexical equivalence in the receptor’s language. Theoretically and in practice, equivalence has been viewed as a basic and central concept and a requirement in the essence of translation. But in the translation of ancient Bible, the issue of non-equivalence in translation proves to be enormously difficult to deal with. This problem appears at all levels from the word level right up to the textual level. In the case of translating what is sometimes referred to as untranslatable due to non-equivalence or lack of equivalence, bible translators either adopt the dynamic equivalence principle using descriptive phrases, transliterate the Bible languages of Hebrew, Greek of Aramaic, or develop new collocations and loan wordss.

In the case of the Bible translation in Malay, all the three translation approaches are used depending on which approach minimizes the loss of semantic meaning in the original. However, it is interesting to note that in the absence of non equivalents in Malay in translating Biblical specific terms and concepts, translators often formulate or coin new words in Malay. Many of these new words are derived from Bible translators would hope that such new words will be adopted into the mainstream Malay dictionary and assist in vocabulary enrichment.

One such particular Biblical concept that is practically semantically difficult to translate into Malay is the word, righteousness. Let’s start with a look at the meaning of the Hebrew terms, tsedeq and tsedaqah for righteous or righteousness. In very broad brush strokes, righteousness in the Old Testament (OT) is used in these cases: a) righteousness (of God's attribute); b) righteousness (in a case or cause); c) righteousness as truthfulness; d) righteousness (as ethically right); e) righteousness (as vindicated).

Christopher J.H. Wright (The Mission of God, p. 365) adds, “The root meaning of the term is probably “straight”, something that is fixed and fully what it should be (in Malay, seharusnya begitu, semestinya, sewajarnya). So it can be a norm or a standard when applied to human actions and relationships; it speaks of conformity to what is right or expected, not in some abstract or absolute generic way but according to the demands of the particular relationship or the nature of the specific situation. Tsedeq or Tsedeqah are in fact highly relational words. Wright also notes that righteousness in the OT is not so much actions or something you do. Rather, it is a qualitative state of affairs of something you aim to achieve.

In Christian theology, the term righteousness has been affirmed to be one of the most difficult themes, but it is very central in the Christian teaching. The word appears more than 700 times in the Bible and there are no Malay equivalents to capture the complex concept associated with this term. Despite the history of 400 years of Bible translation in Malay, translators are still grappling until today to translate the term into Malay that conveys the full semantic meaning of righteousness. Translators have explored using words such as kewajaran, kebenaran, kesalihan, kewarakan and perbenaran.

June Ngoh in her doctorate thesis, Towards Cross-Cultural Cognitive Compatibility in the Malay Translation of Soteriological Terms, wrote: "Of all the alternatives offered for the Malay translation of the term 'righteousness', a recently proposed term 'Kewajaran' seems to be the most promising." She added: "One of the new terms proposed is 'Pewajaran'. In its support, the main argument is that in the court of law, an action that is considered 'justified' is an action 'done on adequate reasons, and sufficiently supported by credible evidence'. The Jabatan Peguam Negara consistently translates this term as ‘Mewajarkan’ which actually means 'to make right, fitting, suitable, compatible'. It is considered applicable here because a person who has been justified in this special theological sense is a person who has been 'made right' in God's sight, according to the requirements of his holy law." (pg. 209 - 210)

Dr June Ngoh’s proposal of kewajaran is a real possibility but many translators could only give a cautious support as kewajaran carries other multiple meanings such as appropriateness, fairness, legitimacy. Besides, it is deemed as too generic. Acceptability of the term could be an issue.

The problem with ‘kebenaran’ is that semantically the word does not represent the original meaning of the righteousness as reflected in original Bible language of Hebrew and Greek or even in English. In the day to day understanding and usage, ‘kebenaran’ means ‘permission, approval or truth’. As a result, the word, ‘kebenaran’ creates the problem of a distorted meaning of such a crucial theological concept of righteousness. To add to the misrepresentation and distortion of the original meaning of the term, ‘kebenaran’ is also used to translate another equally weighty theological concept, truth, in almost all the earlier Malay Bibles. We have one same word, ‘kebenaran’ to define two theologically heavy concepts of truth (αλήθεια) and righteousness (dikaiosuné, δικαιοσύνη) or in Hebrew (tsaddiq, צדקה). Using one same word, ‘kebenaran’, to translate two important biblical concepts of righteousness and truth has left many users and readers perplexed and confused with ‘which word is which’. Many lay readers of the Malay Bible do not make the linguistic demarcation of the two diverse semantic meanings of truth and righteousness.

The real issue arises when both the words righteousness and truth occur side by side in the Bible text. An example of such occurrence is found in Ephesians 5:9, “...for the fruit of the Spirit in all goodness and righteousness (dikaiosynē) and truth (alētheia). The Terjemahan Baru, published by Lembaga Alkitab Indonesia, which was widely used here in Malaysia in the absence of a good Malay Bible, circumvented this translation issue by using another term, keadilan to translate the original word, dikaiosuné (righteousness) when throughout the same Bible for the same specific Greek word, ‘kebenaran’ is used. The problem with this option, which is an abdication of the translator’s responsibility, is that it leaves the determination of its actual meaning entirely to the reader.

Not surprisingly, when a new translation team was assembled to undertake a fresh translation of the Malay Bible known as Alkitab Versi Borneo (AVB) in 1998, the translators felt warranted to review the existing long established use of the term, ‘kebenaran’. In one sense, since it is a fresh translation, translators were freer to experiment with the coining of a new word. Hence, after much deliberation and critical analysis, the team decided to coin a new Malay word, that is, ‘perbenaran’ to translate the word, ‘righteousness’. In the AVB, the phrase ‘to be make righteous’ is translated as ‘diperbenar’. The word has been field-tested and a good number of native readers welcome it enthusiastically. As the newly coined term was derived from the root word, ‘benar’', they could fully comprehend the meaning. The word-formation of this new term, ‘perbenaran’, from the root word, ‘benar’ exemplifies the derivational process of the Malay affixation and appears to encompass well the full cognitive implications of ‘righteousness’. To help explain the new coinage of the term ‘perbenaran’, a short explanation is provided in the footnote of the new translation of the AVB Malay Bible. In this way, the complexity of all levels of meaning is accounted for in the understanding of the text. Incorporating an extensive system of footnotes which help reader obtain proper background information is necessary to guarantee that the translation will not be misunderstood.

Below is an enthusiastic response from an anonymous scholar who hails from a Bahasa-speaking church:

“Both tsedeq and dikaiosunē are discoursed by Hebrews author in ‘forensic’ terms contextually (as documented by historical witness: Church Fathers, Luther, early protestant reformists, the puritans and even held by the Fundamentalist evangelicals of early-mid 20th Century) which have no satisfactory Malay equivalents.

For now, I suggest applying it directly semantically into our grasp.

If need be, we may need to additionally qualify our usage of ‘Perbenaran’ when we teach/preach/translate songs until such time it is accepted as part of common BM vernacular. However, even on its simplistic merit, it aids us now to exegete and expound scriptures especially Romans and Hebrews in Bahasa (Malay) more profoundly then ever before possible!”

c) The socio-cultural factor

The socio-cultural factor in translation is one most crucial problems faced by any translator trying to bridge the span between quite diverse cultures. In the case of the Malay translation of the Bible, translators have to constantly revise the text as they constantly grappled with new words and phrases to translate objects, belief system, habits, customs that are so deeply rooted in the biblical source culture and so specific and exclusive that they have no equivalent in the target culture. The discrepancy in cultural beliefs, norms and linguistic expression between the Bible cultures and the Malay language often necessitates the need for innovative translation strategies.

One example which has continued to trouble translators in the diverse culture of Malaysia is the translation of the Greek word, “συναγωγή” (synagogue). Synagogues were also used as places for civic gatherings but the focus in most of the Bible passages is that the synagogue is a place of meeting for worship and religious instruction in the Jewish faith. The issue here is that in many cultures and languages, the term synagogue is literally unknown or heard. Translators frequently use a transliteration of the term synagogue. In some languages a descriptive equivalent is used, for example, ‘in houses of worship used by Jews’ or ‘in Jewish buildings for worship.’

In Malaysia, there are many specific designations for the places of worship with precisely defined functions and features. Different words are used to define the different places of worship of different races and religions. For example, kuil is used to translate the Chinese or India temple and gereja for the Christian place of worship and masjid for Muslims.

Over the years of the Malay translation of the Bible, different words have been used to translate synagogue in different translations and revisions. For example, the Klinkert translation of 1879 used two Arabic words, “mesjid” (mosque) and also “Kaaba” for synagogue and Jewish temple respectively. Instead of rendering words by their equivalents in the source language culture, Klinkert used local existing words that he thought perhaps would aid the comprehension of the place of worship in the source language culture. While these two words, “mesjid” and “Kaaba” could provide somewhat some semblance of what a synagogue is, modern readers would be shocked at such renderings that are conceptually and symbolically so dissimilar.

Moving forward from the Klinkert’s translation, the 1987 of the Today’s Malay Version, rumah ibadat (house of worship) is used in line with the phrase used in the Terjemahan Baru of the Indonesia Bible. Of all the different lexical variants used to translate the term synagogue, rumah ibadat is the most widely used and accepted though it is not a satisfactory phrase to reflect the successful cross-cultural transfer of the meaning of synagogue in the target language culture.

The most recent version of the 2016 Malay Bible, Alkitab Versi Borneo, opted for a new word, saumaah, an Arabic loan word which has been fully incorporated into the Malay language. This is a term or expression recognized as an established equivalent in the Malay language to denote the term synagogue. It is noteworthy to mention here that the word saumaah was never used before in all the past Malay translations of the Bible but it is an apt equivalent that reflects a close adherence to the literal representation of what a synagogue is in source language culture. Perhaps, in the earlier days, saumaah was not codified as a word in the Malay vocabulary until the recent times where local media and articles make frequent references to synagogue when reporting on the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The problem of correspondence in translation and differences between cultures may sometime cause more sociocultural complications than non equivalent lexicons in the target language. One example is the use of bin and binti (son and daughter of) to translate the lineage of descendants.

The AVB translation team of translators and consultants made a deliberate decision to abort the traditional use of bin and binti in a way that reflects complete translation integrity, sensitivity to the unique sociocultural situation and opted for anak. For example the AVB uses Yosua anak Nun (Joshua son of Nun) instead of Yosua bin Nun. In dropping the bin and binti in AVB, the translators opted for neutrality and to encompass all Malay speaking groups. The reason is largely a sociocultural consideration. Generally the public perception especially in Peninsula Malaysia is, the use of bin and binti denotes the Malay Muslim ethnoreligious identity.

Another word that gives a more successive transfer of meaning from the source language culture and for an effective cross cultural communication is the use of the word, maghrib, a Arabic loan word to mean evening after sunset. The Shellabear version of the Malay Bible uses this word. The word is also used by other translations in Indonesia such as the Kitab Suci Taurat dan Zabur. Another word for dusk, senja does not adequately translate the meaning of the Hebrew word, hā-‘ā-reḇ, as used in the context of a person that is unclean until the evening and in a state preventing him from participating in the ritual activities of the community. This condition continues until the setting of the sun. In some languages “until the sun goes down (or, disappears) or “until the end of the day” is the most natural translation of the phrase until the evening. But translators must remember that for the Jews the day ended with the setting of the sun. The translation should not give the impression that the state of impurity continues until midnight or until the following morning. If we use senja, misunderstanding of the text is likely to occur.

In the words of Margherita Ulrych: “Translating is a cross-linguistic and cross-cultural communicative process between SL [source language] writer and TL [target language] reader, which takes place at textual level within a social-cultural context. Translators act as mediators between the SL and TL cultures, as interpreters, that is, of the SL message and emitters of the same message in the TL. Since language is an integral part of culture, translators need to be not only proficient in two languages but also familiar with two cultures; ideally, they are not only bilingual but also bicultural.”

3. Summary

The religious language in Malay used by the Christian community over the last four centuries has clearly developed into a distinct linguistic variety. Bible translators continue to probe for appropriate words and other linguistic forms to satisfy the demand for accuracy of meaning cognitively. When coined words are used as in the case of the word, “perbenaran,” a short explanation should be given to describe the expressive, evoked and associative meanings. While some of these words are not widely used or understood outside the church domain or incorporated in any of the public Malay dictionaries, they remain integral words that are used by the Christian community and contribute to the enrichment and expansion of the treasury of the Malay terminologies.

Table 2 - An Example of Lexical Changes Over Time in the Malay Bible (1733-2016)

|

Leydekker (1733) |

Klinkert (1879) |

Shellabear (1929) |

Bode (TL) 1938, 1958 |

Berita Baik (1987) |

AVB (2016) |

English Equivalent |

|

Al Maktub |

Kitaboe'lkoedoes |

Kitab-kitab yang kudus |

Kitab-kitab yang kudus |

Kitab Suci |

Kitab Suci |

Holy Scriptures |

|

Awrang Mesehhij |

Orang Masehi |

Orang Masehi |

Orang Kristen |

Orang Kristian |

Orang Kristian |

Christian |

|

Dadjal |

adDadjal |

Lawan al-Masih |

Dajal |

Musuh Kristus |

Dajal |

Antichrist |

|

Kaxbah (Ka’aba) |

Roemah Allah |

Ka'bah |

Bait Allah |

Rumah Tuhan |

Bait Suci |

Temple |

|

Kalamu’lhayat |

Sabda penghidoepan |

Perkataan yang memberi hidup |

Firman yang memberi hidup |

Firman yang memberikan hidup |

Firman yang memberikan hidup |

The Word of Life |

|

Kanisah |

Masdjid |

Rumah tempat sembahyang |

Rumah sembahyang |

Rumah Ibadat |

Saumaah |

Synagogue |

|

Katib |

Pandita Torat

|

Pendeta Taurit |

Ahli Taurat |

Ahli Taurat |

Ahli Taurat |

Teachers of the law |

|

Kitab (Al) Hajat |

Kitaboe'lhajat |

Kitab Hayat |

Kitab Hayat |

Kitab Orang Hidup |

Kitab Hidup |

The Book of Life |

|

Mawlana |

Rabi |

Rabbi |

Rabbi |

Rabbi |

Rabbi |

Teacher; Rabbi |

|

Mukalis |

Djoeroe-salamat |

Juru-selamat |

Juruselamat |

Penyelamat |

Penyelamat |

Savior |

|

Rohhu-'lkhudus |

Rohoe'lkoedoes |

Ruhu’lkudus |

Ruhulkudus |

Roh Kudus |

Roh Kudus |

Holy Spirit |

|

Xisaj 'Elmesehh |

Isa Al Masih |

Isa Al Maseh |

Yesus Kristus |

Yesus Kristus |

Yesus Kristus |

Jesus (the) Christ |

|

Zabur |

Zaboer |

Zabur |

Zabur |

Mazmur |

Mazmur |

Psalm |

|

'elsalam xalejkom |

Assalam alaikoem |

Sejahteralah kamu |

Sejahteralah kamu |

Salam Sejahtera |

Damai Sejahtera kepada kamu |

Peace be with you |

|

'ija 'itu Permandij |

Jahja pembaptis |

Yahya Pembaptis |

Yahya Pembaptis |

Yohanes Pembaptis |

Yohanes Pembaptis |

John the Baptist |

Common Errors of Translation into Bahasa Malaysia, Goh Lay Hua